From the Desk of Consul General Osumi

2024/1/9

Essay Vol. 4

~Reflections on the New Year Bell-ringing Ceremony and

Double Exhibitions of Japanese art:“The Heart of Zen” and “Murakami: Monsterized”~

~Reflections on the New Year Bell-ringing Ceremony and

Double Exhibitions of Japanese art:“The Heart of Zen” and “Murakami: Monsterized”~

January 9, 2024

Yo Osumi

Consul General of Japan in San Francisco

New Year Bell-ringing Ceremony

On New Year's Eve last year, the 38th New Year Bell-ringing Ceremony was held at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. My son, a high school senior living alone in Tokyo, was in San Francisco for winter vacation, so all four of us went to the ceremony. Upon entering the Asian Art Museum and entering the main hall (Samsung Hall) at the top of the stairs, we found more than 300 people, reflecting a diverse racial and ethnic composition, already in attendance. The seats provided were not enough and the standing room crowd was doubly surrounded by people on all sides. The Great Bell was placed majestically in the middle of the hall.

At the ceremony, Chief Curator Mintz first explained the Buddhist concept of the 108 worldly desires and the Japanese tradition of ringing the bell 108 times in the hope of eliminating them.

I explained the significance of the New Year's bell in the Japanese mindscape, as well as the events around the New Year, such as deep cleaning on New Year’s Eve, the first dream of the new year, and shopping for a lucky new year mystery bag. I then shared my family’s Zen meditation experience during a visit to Eiheiji Temple, which was built in the mountains of Fukui in the 13th century by Zen grandmaster Dōgen, founder of the Sōtō sect of Zen Buddhism, and introduced Abbot AKIBA Gengo, a monk at the Kojin-an Zen temple in Oakland. He went through ascetic Zen training for eight years at Eiheiji Temple, then came to Oakland, where he has hosted Zen meditation morning meetings every day for more than 20 years.

Afterwards, Dr. Allen, the museum's curator of Japanese art, led us on a tour of the museum, where we saw Abbot Akiba reciting a sutra in front of a statue of the Buddha displayed in the Japanese section. He said, "I thought the Buddha might be lonely, so I read him a sutra.” My eldest son was impressed by his display of vibrant faith.

According to Professor Francis Fukuyama, an American political scientist, “mindfulness” is based on East Asian and Zen ideas. My second son's school also believes in mindfulness, and every morning they have a few minutes of "reflection," during which they sit in a circle on the floor of the gymnasium and meditate on special cushions known Zafu, the shape of which is identical to those used by our family when we went to Eiheiji Temple to do zazen, or Zen meditation. Incidentally, the school also uses gongs as its school bell. It was a glimpse into the quiet influence of Japanese and Asian culture on a small part of American social landscape.

Tradition and Modernity: Exhibition of Daitokuji Temple's Ink Painting Masterpieces and Takashi Murakami

Two contrasting special exhibitions on Japan, The Heart of Zen—the international debut of the masterpieces "Six Persimmons" and "Chestnuts"—and Murakami: Monsterized, an exhibition of contemporary pop art by Takashi Murakami, were simultaneously on view at the Asian Art Museum, and both were the talk of the town. Together with the exhibition on Yayoi Kusama, there were three Japan-related exhibitions in the city.

The first was an exhibition of persimmon and chestnut paintings by Muqi (Mokkei in Japanese), a revered ink painter of the late 13th century in China. At some point in the 15th or 16th century, they were shipped to Japan and eventually donated to Daitokuji Ryōkōin Zen Temple in Kyoto, where they have been kept ever since. They were designated as Important Cultural Properties in 1919. The temple is home to many national treasures and important cultural properties, but they are very rarely seen by the public. This was the first time in history that works from the temple's collection could be seen outside of Japan. Due to time constraints on lighting—which, if too harsh, could damage the paintings—only the persimmon paintings were on display in the first half of the exhibition, and the chestnut paintings in the second half. But for three days, both paintings were on display side by side. That special three days drew a huge number of art connoisseurs, whose long line encircled the Asian Art Museum.1

A single hanging scroll of an ink painting, quietly displayed under dim lighting at the back of the large room of the special exhibition. It is the ultimate in simplicity, stripped down to the bare essentials. The museum's exhibition is a tasteful expression of a world of quietness, purity, and a state of stillness. The phrase, "The uniqueness of Japanese culture lies in the development of this quiet and somehow lonely world, or in the development of an aesthetics that denies a sense of color," from Omotesenke's website, "Chanoyu: Heart and Beauty," is a perfect description of this world.

Having spent my life moving from one foreign country to another, the question of how to explain Japan has been a perennial challenge for me. Although it is clear that the Japanese tradition is different from the monotheistic view of a world created by God and ruled by humans as surrogates with dominion over animals and plants, how, then, do we perceive its differences from Chinese civilization and culture?

For me, the difference between Japanese and Chinese ink painters, as explained by Kure Motoyuki, former curator at the Kyoto National Museum, and quoted in the explanatory note of the special exhibition, was intriguing:

For the Japanese, and in particular for chanoyu tea connoisseurs, nature was best rendered into an immersive experience through amorphous, bleeding ink. In contrast, the Chinese viewed paintings with the hope of becoming one with the universe, experiencing the ethos of heaven and earth in accordance with orderly established norms. What we see, then, in the works of Muqi, is the essential difference between Japanese and Chinese perceptions of ink painting.

I feel that the Chinese, who have lived under a great civilization (or civilizations) with the rise and fall of people and dynasties, are conscious of "heaven" or the "mandate of heaven," and tend toward grandeur and orderly beauty, while the Japanese are more closely connected to nature and, as in the case of the recent earthquakes, are compelled to oblige themselves to the tyranny of nature. After all, Japan is an island country of the Far “East;” the next stop beyond Korea after Japan is Hawaii, thousands of miles away.

According to the explanatory note, Muqi’s ink paintings were criticized as “coarse, ugly and lacking in ancient techniques,” and the Chinese rejected them as “unorthodox and dissident.” He was forgotten during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Indeed, the fact that the emperors of the Qing Dynasty, who were so passionate about collecting Chinese artifacts—many of which are housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei—had only one work by Muqi in their collection is quite telling.

There is a tradition of waka poetry literature in Japan, in which “wabi” and “sabi” have become invaluable aesthetics. “Wabi” (from the verb wabu, meaning “to feel depressed;” “to find [something] hard;” “to fall;” etc.) and “sabi” (from the verb sabu, meaning “to grow old;” “to fade away”), which originally indicated negative feelings, conversely came to be valued and transformed into words that evoked beauty. The Omotesenke website explains that in the world of waka poetry from the Heian period to the Kamakura period, the aesthetic senses of quietness, simplicity, and dryness were brought to life. Muqi’s ink paintings, which depict the beauty of nature as it is, match this unique Japanese aesthetic sense.

This is why Muqi’s works have been quietly stored at Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto for hundreds of years. At the end of the year, here in the foreign land of San Francisco, I was able to encounter these paintings. It was deeply moving.

Takashi Murakami Exhibition "Murakami-Monsterized"

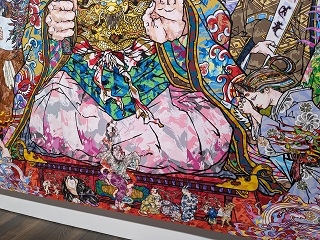

I am ashamed to confess that I was ignorant of Takashi Murakami. The popularity of the Takashi Murakami exhibition here was quite impressive. The younger generation, especially children, seemed to be very attracted to the vibrant cartoon, pop, yōkai, and character elements. There are countless illustrations of his characteristic flower paintings, but only a few were smiling! Finding these rare smiles became a quiet trend among the children who came to see the exhibition, and they were running around giggling as they stared intently at the walls and floor.

I am always interested in the question of what, exactly, is the universal appeal of anime that attracts people around the world. What is the added value of Japanese anime and its influence on world culture? I was therefore curious to know what attracts people to the art of Mr. Murakami, who is a big fan of anime and a self-proclaimed otaku.

Murakami, who received a scholarship for a year in New York after graduating from Tokyo Geidai (Tokyo University of the Arts), later spent time on the West Coast as a visiting scholar at UCLA. He has been associated with American society, and he has created works that resonate with the Black Lives Matter movement.2 On the other hand, while viewing the exhibit, I found it very illuminating that Mr. Murakami is a graduate of the Japanese Painting Department at the Tokyo University of the Arts. While some of Murakami's works are futuristic, there is something very Japanese about the mindscape of his huge new work, which the museum has been eagerly awaiting, with yōkai, beckoning cats, Kabuki actors, and other characters.

I am ashamed to confess that I was ignorant of Takashi Murakami. The popularity of the Takashi Murakami exhibition here was quite impressive. The younger generation, especially children, seemed to be very attracted to the vibrant cartoon, pop, yōkai, and character elements. There are countless illustrations of his characteristic flower paintings, but only a few were smiling! Finding these rare smiles became a quiet trend among the children who came to see the exhibition, and they were running around giggling as they stared intently at the walls and floor.

I am always interested in the question of what, exactly, is the universal appeal of anime that attracts people around the world. What is the added value of Japanese anime and its influence on world culture? I was therefore curious to know what attracts people to the art of Mr. Murakami, who is a big fan of anime and a self-proclaimed otaku.

Murakami, who received a scholarship for a year in New York after graduating from Tokyo Geidai (Tokyo University of the Arts), later spent time on the West Coast as a visiting scholar at UCLA. He has been associated with American society, and he has created works that resonate with the Black Lives Matter movement.2 On the other hand, while viewing the exhibit, I found it very illuminating that Mr. Murakami is a graduate of the Japanese Painting Department at the Tokyo University of the Arts. While some of Murakami's works are futuristic, there is something very Japanese about the mindscape of his huge new work, which the museum has been eagerly awaiting, with yōkai, beckoning cats, Kabuki actors, and other characters.

I felt that the new large-scale works in the special exhibition were filled with a zeal to depict all aspects of the East and West as East-Meets-West. The composition of a sailing ship coming in on the waves from the Age of Discovery, the giant underworld god King Enma judging good and evil after death, and the exposed humans positioned vertically alongside him reminded me of purgatory in Dante's Divine Comedy or the Last Judgment in Michelangelo's work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Dr. Allen's commentary was also a very refreshing discovery for me.

To Make the World Diverse and Rich: Our Role of Interacting with Foreign Countries and Weaving Japanese Culture into the future of the World

The black-and-white ink paintings of Muqi, who became a "painting sage" of the sense of beauty that Japan has cultivated. The paintings of Takashi Murakami, who grew up with anime that projected something of the Japanese aesthetic sense and created a world full of color, who paints yōkai or ghosts, trying to connect East and West by means of an original Japanese identity. It is wonderful that these two contrasting exhibitions were held at the same time and generated so much interest in this part of the world.

The recent enthusiasm for travel to Japan in this area has been very strong. Even though washoku (Japanese food) and powder snow in Hokkaido may be the gateway to Japan, once you enter Japan, you will be amazed by the cleanliness, safety, and kindness of its people. That would surely lead one to an admiration of the aesthetics of Japanese culture. I am convinced that Japanese civilization has great value to contribute to the world, and that Japanese culture makes the world's culture richer and more diverse. However, nothing can be taken for granted. We Japanese must be aware of that preciousness and weave our culture into the future.

And just as Muqi's works came to Japan and Murakami went to the U.S., exchanges overseas are of paramount importance. Many Japanese expats in this area and all those who cherish Japan offer much to the world. Regardless of nationality, ethnicity and religion, they are at the forefront of those exchanges. I deeply respect and appreciate the great role they play.

-----------------------------------------

1.https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/persimmons-chestnuts-sf-asian-art-museum-18543045.php

2.https://hbr.org/2021/03/lifes-work-an-interview-with-takashi-murakami

To Make the World Diverse and Rich: Our Role of Interacting with Foreign Countries and Weaving Japanese Culture into the future of the World

The black-and-white ink paintings of Muqi, who became a "painting sage" of the sense of beauty that Japan has cultivated. The paintings of Takashi Murakami, who grew up with anime that projected something of the Japanese aesthetic sense and created a world full of color, who paints yōkai or ghosts, trying to connect East and West by means of an original Japanese identity. It is wonderful that these two contrasting exhibitions were held at the same time and generated so much interest in this part of the world.

The recent enthusiasm for travel to Japan in this area has been very strong. Even though washoku (Japanese food) and powder snow in Hokkaido may be the gateway to Japan, once you enter Japan, you will be amazed by the cleanliness, safety, and kindness of its people. That would surely lead one to an admiration of the aesthetics of Japanese culture. I am convinced that Japanese civilization has great value to contribute to the world, and that Japanese culture makes the world's culture richer and more diverse. However, nothing can be taken for granted. We Japanese must be aware of that preciousness and weave our culture into the future.

And just as Muqi's works came to Japan and Murakami went to the U.S., exchanges overseas are of paramount importance. Many Japanese expats in this area and all those who cherish Japan offer much to the world. Regardless of nationality, ethnicity and religion, they are at the forefront of those exchanges. I deeply respect and appreciate the great role they play.

-----------------------------------------

1.https://www.sfchronicle.com/entertainment/article/persimmons-chestnuts-sf-asian-art-museum-18543045.php

2.https://hbr.org/2021/03/lifes-work-an-interview-with-takashi-murakami

Recommended Information

- Essay Vol.1 (2023.11)

- Essay Vol.2 (2023.11)

- Essay Vol.3 (2023.12)

- Essay Vol.5 (2024.02)

- Essay Vol.6 (2024.03)

- Essay Vol.7 (2024.04)

- Essay Vol.8 (2024.04)

- Essay Vol.9 (2024.05)

- Essay Vol.10 (2024.06)

- Essay Vol.11 (2024.07)

- Essay Vol.12 (2024.08)

- Essay Vol.13 (2024.09)

- Essay Vol.14 (2024.10)

- Essay Vol.15 (2024.10)

- Essay Vol.16 (2024.11-12)

- Essay Vol.17 (2025.01)

- Essay Vol.18 (2025.02)

- Essay Vol.19 (2025.03)

- Essay Vol.20 (2025.04)

- Essay Vol.21 (2025.05)

- Essay Vol.22 (2025.06)

- Essay Vol.23 (2025.07)

- Essay Vol.24 (2025.08)