From the Desk of Consul General Osumi

2025/7/25

Essay Vol. 23

~What is Japan? What is Japanese?~

~What is Japan? What is Japanese?~

July 25, 2025

Yo Osumi Consul

General of Japan in San Francisco

Yo Osumi Consul

General of Japan in San Francisco

"What kind of country is Japan, I wonder?" As someone born and raised in Japan, I had never thought about this question before. However, after joining the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and experiencing cultural disorientation, I found myself reflecting on Japan and the Japanese people. Learning the way of tea upon returning to Tokyo and belatedly reading Eastern classics were both part of a journey in search of an answer to that question.

While stationed in San Francisco, I’ve had many opportunities to give speeches as Consul General (I counted—over 40 just in the first half of this year!). As Consul General, I’m naturally expected to speak about "Japan." So this time, I’d like to trace back through some of my past speeches and explain my own understanding of "Japan.”

The Women Who Cultivated Japan’s Aesthetic Sense: Speech at the Northern California Cherry Blossom Festival Queen Program

Spring in Northern California begins with the Cherry Blossom Festival. It’s a celebration filled with the history and sentiments of Japanese Americans, and the Cherry Blossom Queens are its shining stars. The Queen Program, which selects the young women who grace events like the Festival’s Grand Parade, is not just about glamour; it’s a competition that chooses future community leaders who embody intelligence and leadership. When I gave a speech in front of the contestants at the opening of last April’s program, I read a waka poem by Akiko Yosano, a poet of the Meiji era:

「清水へ 祇園をよぎる 桜月夜 こよひ逢ふ人みな美しき」

Kiyomizu e / Gion wo yogiru / Sakurazukiyo / Koyoi au hito / Mina utsukushiki

Strolling past Gion / To Kiyomizu / Under moonlit cherry blossoms / Every person I meet / Is beautiful to gaze on

Kiyomizu e / Gion wo yogiru / Sakurazukiyo / Koyoi au hito / Mina utsukushiki

Strolling past Gion / To Kiyomizu / Under moonlit cherry blossoms / Every person I meet / Is beautiful to gaze on

Yosano was a pioneering female poet of the Meiji period (1868-1912) and a successor to the Japanese literary tradition that has long been captivated by the beauty of cherry blossoms. Female writers of the Heian period (784-1185) expressed the importance of fleeting beauty and the subtle nuances that linger around casual words, captured through the flowing lines of the newly invented hiragana script (as opposed to the orderly logographic organization of Chinese kanji). Donald Keene, a renowned scholar of Japanese studies, noted that the aesthetic sensibilities these women cultivated became a shared cultural heritage of the Japanese people. In my speech, I encouraged the Queens to follow in the footsteps of these predecessors who elevated the quintessential sense of beauty and fly high as the next generation of leaders.

Rich Emotion and the Tradition of Waka Poetry: Speech at the Emperor’s Birthday Reception

In my view, Japan’s rich emotional depth is encapsulated in the lineage of waka poetry. One tradition that embodies this is the Imperial New Year Poetry Reading (Utakai Hajime), which records show was first held on January 15th, 1267, meaning it has continued for nearly a thousand years.

At last year’s and this year’s Emperor’s Birthday receptions, I introduced this traditional event. As an example of how the spirit of our ancestors lives on today, I shared Her Imperial Highness Princess Aiko’s poem from the Utakai Hajime:

「幾年(いくとせ)の難き時代を乗り越えて和歌のことばは我に響きぬ」

Ikutose no / Kataki jidai wo / Norikoete / Waka no kotoba wa / Ware ni hibikinu

"Surviving centuries of hardship / the words of waka poems / touch my heart today.”

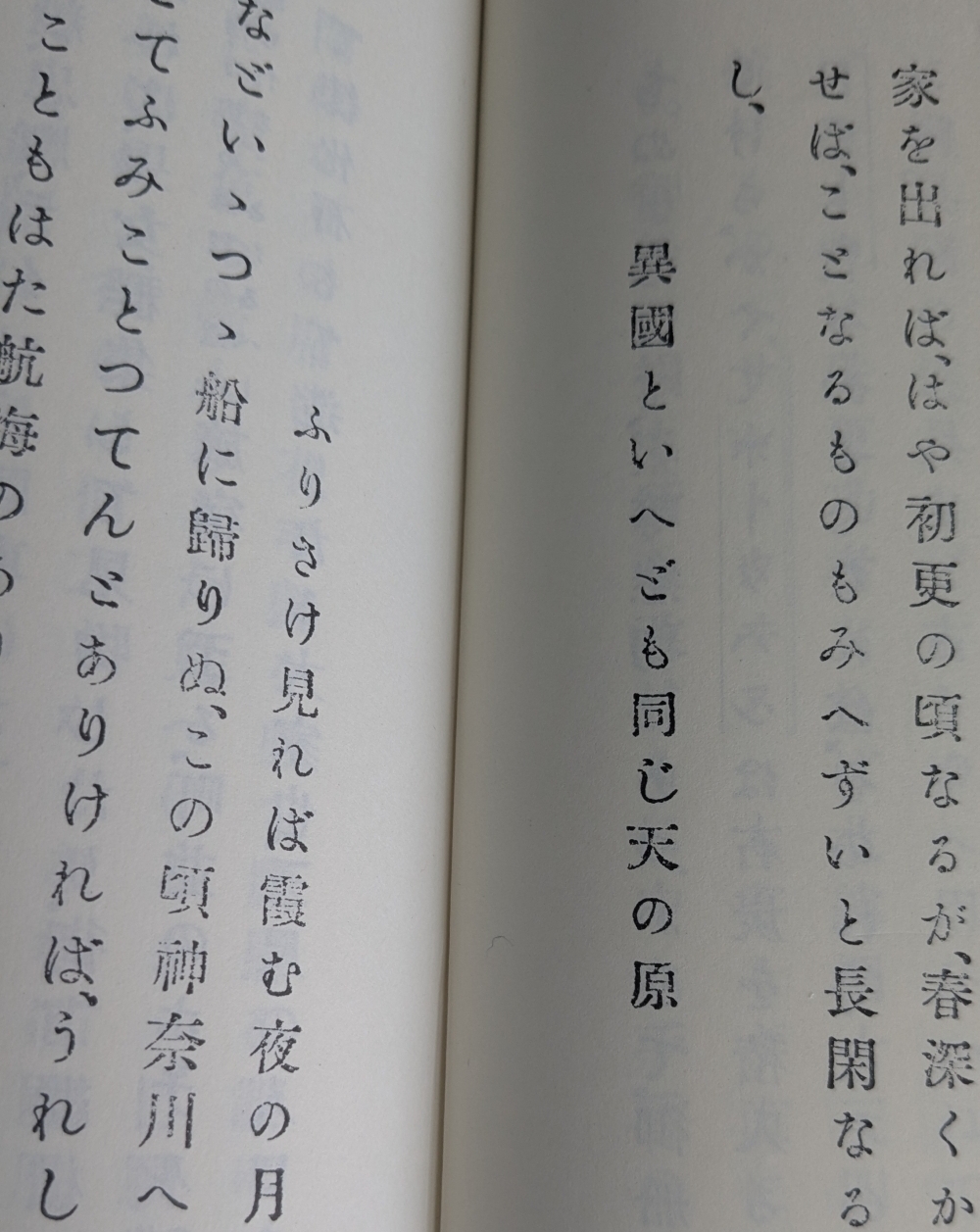

The official logbook of the Kanrin Maru, the Japanese ship carrying the first modern delegation to the United States, which arrived in San Francisco in 1860, includes a waka poem composed while gazing at the moon in San Francisco:

「異国 (ことくに) といへども同じ天の原 ふりさけ見れば霞む夜の月」

Kotokuni to / Iedomo onaji / Amanohara / Furisake mireba / Kasumu yonotsuki

“Even in distant lands it is the same heavens, the same moon we gaze at through the misty night sky.”

The poet likely identified with Abe no Nakamaro, who traveled to Tang China as a young envoy at age 19 during the Nara period (710-794), gained great renown, and despite many attempts, never returned to Japan, passing away at 72. Nakamaro once looked up at the foreign night sky and wrote:

「天の原ふりさけ見れば春日なる三笠の山に出でし月かも」

Amanohara / Furisake mireba / Kasuganaru / Mikasa no yama ni / Ideshi tsukikamo

“When I look up at / the wide-stretched plain of heaven, / is this the same moon / that rose on Mount Mikasa / above the Kasuga Shrine? ”

Amanohara / Furisake mireba / Kasuganaru / Mikasa no yama ni / Ideshi tsukikamo

“When I look up at / the wide-stretched plain of heaven, / is this the same moon / that rose on Mount Mikasa / above the Kasuga Shrine? ”

In the 2024 Utakai Hajime, a poem by a resident of Los Angeles was also selected:

「かの日々に移り来し人等耕しし 大和と呼ぶ里アマンドの花」

Kanohibi ni / Utsurikishihitora / Tagayashishi / Yamato to yobu sato / Amando no hana

In days gone by / Those who came before / cultivated the home called Yamato / Almond blossoms

Kanohibi ni / Utsurikishihitora / Tagayashishi / Yamato to yobu sato / Amando no hana

In days gone by / Those who came before / cultivated the home called Yamato / Almond blossoms

Devotion to Nature: Speech at the Disaster Prevention Forum

What I felt when I experienced the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 was a sense of resignation that we have no choice but to submit to the overwhelming power of nature. In my remarks at our office’s Disaster Prevention Forum held in San Francisco last October, I expressed that I felt the helplessness of humanity.

At the same time, I believe that a sense of harmony, or the feeling that we are part of nature, as well as a reverence for nature, lies deep within the hearts of Japanese people. hThis view was echoed recently when I invited Dr. Scott D. Sampson, a Canadian-American paleontologist and the Executive Director of the California Academy of Sciences, for lunch. Dr. Sampson has criticized the tendency of many people to view nature as something external and controllable. He posits that humans are part of nature, and rather than seeing nature as something to dominate, we must learn to treat it like a relative, cherishing and embracing it.

On “Ma” and Asymmetry: Speech at the Ikebana Demonstration Event

As I wrote in the previous issue in this series, my wife Misao co-hosted an ikebana demonstration titled “One World: Two Voices: An Ikebana Journey” with the San Francisco Garden Club, featuring a collaboration between the Ohara and Sogetsu schools of ikebana. In her opening remarks, she contrasted Western flower arrangements with Japanese ikebana using the concepts of “filled space vs. ma (negative space)” and “symmetry vs. asymmetry.”

Lavish Western flower arrangements often overflow from their vases, creating a sense of abundant fullness. Similarly, when attending American football, baseball, or basketball games, the venues are constantly filled with sound, leaving no room for even a moment of silence or contemplation. In contrast, ikebana values ma (the space between flowers), encouraging tranquility and leaving room for personal imagination within the arrangement.

While perspective and symmetry intuitively convey beauty, asymmetry does not immediately appeal to the senses. Yet, when this asymmetry is elevated into an aesthetic sensibility and shared, it reveals a unique characteristic of Japanese culture.

What I felt when I experienced the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 was a sense of resignation that we have no choice but to submit to the overwhelming power of nature. In my remarks at our office’s Disaster Prevention Forum held in San Francisco last October, I expressed that I felt the helplessness of humanity.

At the same time, I believe that a sense of harmony, or the feeling that we are part of nature, as well as a reverence for nature, lies deep within the hearts of Japanese people. hThis view was echoed recently when I invited Dr. Scott D. Sampson, a Canadian-American paleontologist and the Executive Director of the California Academy of Sciences, for lunch. Dr. Sampson has criticized the tendency of many people to view nature as something external and controllable. He posits that humans are part of nature, and rather than seeing nature as something to dominate, we must learn to treat it like a relative, cherishing and embracing it.

On “Ma” and Asymmetry: Speech at the Ikebana Demonstration Event

As I wrote in the previous issue in this series, my wife Misao co-hosted an ikebana demonstration titled “One World: Two Voices: An Ikebana Journey” with the San Francisco Garden Club, featuring a collaboration between the Ohara and Sogetsu schools of ikebana. In her opening remarks, she contrasted Western flower arrangements with Japanese ikebana using the concepts of “filled space vs. ma (negative space)” and “symmetry vs. asymmetry.”

Lavish Western flower arrangements often overflow from their vases, creating a sense of abundant fullness. Similarly, when attending American football, baseball, or basketball games, the venues are constantly filled with sound, leaving no room for even a moment of silence or contemplation. In contrast, ikebana values ma (the space between flowers), encouraging tranquility and leaving room for personal imagination within the arrangement.

While perspective and symmetry intuitively convey beauty, asymmetry does not immediately appeal to the senses. Yet, when this asymmetry is elevated into an aesthetic sensibility and shared, it reveals a unique characteristic of Japanese culture.

What is Japan? A Lecture for Stanford Graduate Students

The ideas mentioned above were brought together in a lecture I gave this April at the request of Professor Kiyoteru Tsutsui of Stanford University. The audience consisted of graduate students selected as Knight-Hennessy Fellows, and the lecture was part of their first preparatory session for a study tour to Japan. To these young students, many of whom had never been to Japan, I presented a conceptual overview of the country through four lenses: continuity; the lingering influence of animistic thinking; diversity; and aesthetic sensibility.

1. Continuity – A Defining Characteristic of Japan

Continuity is a key concept that exemplifies Japan’s cultural identity. One of the most prominent examples is the Imperial Family. The current Emperor is the 126th in a long line of succession, making Japan’s imperial household the oldest continuous monarchy in the world. This tradition also includes the art of waka poetry, with successive emperors composing their own poems:

The Ogasawara school of archery dates back to the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and its grandmaster is now the 31st of his lineage. Likewise, the head masters of the main tea ceremony schools—Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanokōjisenke—originating in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1603), have each continued for 16, 16, and 14 generations respectively. The confectionery company Toraya has a history of over 500 years, and it still features traditional sweets from various eras, such as tsubaki mochi from 1651, aoyagi from 1836, and chitose mochi from 1918.

The reason for this longevity of tradition lies in Japan’s geographical isolation as an island nation, which has largely shielded it from foreign invasions. Additionally, since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate, Japan experienced over 400 years with minimal internal warfare. Compared to the UK, another island nation only about 20 miles from continental Europe across the Strait of Dover, Japan is much more remote: about 120 miles from the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, with about 550 miles separating Shanghai and Fukuoka. This favorable environment allowed Japanese culture to preserve its traditions. The societal emphasis on tradition, conservatism, mastery of skills, and the artisan spirit has profoundly influenced the development of Japanese society and culture.

2. The Influence of Animism

When humans were still hunter-gatherers, they lived as part of nature. They believed that spirits and consciousness resided in all things—trees, stones, rivers, mountains—and worshipped nature itself. Over time, through polytheism and eventually monotheism, religions like Christianity and Islam spread across the world, and animism was largely pushed aside, though traces of it remain in many regions.

However, in Japan, animistic thinking has remained deeply rooted, primarily through Shinto. This has preserved ideas such as coexistence with nature and unity with the natural world. For example, the sacred object of worship at Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara, considered Japan’s oldest shrine, is Mount Miwa itself. Similarly, Hayao Miyazaki’s films like My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke were born from this cultural backdrop. Personally, I was reminded of the awe we should hold toward nature through the experience of the Great East Japan Earthquake. This way of thinking feels closer to the worldview and perception of nature held by ancient societies, rather than the relatively newer frameworks of monotheistic religions—in which God created the world in seven days and placed humans at the top of the hierarchy—or Chinese philosophy, which developed logical systems to unify central regions and exercise authority.

I once asked a Japanese person with deep knowledge of anime and long experience living abroad why Japanese anime resonates so strongly. Their answer was fascinating: “Young people in the U.S. have realized that adults lie. They don’t live in a world of simple good-versus-evil dualism. Good people have flaws, and even villains can be sympathetic. Anime reflects this more complex reality. In a way, American youth may find value in anime.” This brings to mind the perspective of Dr. Sampson and his insights described earlier in this essay: that humans are part of nature and must learn to love and cherish it as if it were family. I believe this worldview is profoundly meaningful.

The ideas mentioned above were brought together in a lecture I gave this April at the request of Professor Kiyoteru Tsutsui of Stanford University. The audience consisted of graduate students selected as Knight-Hennessy Fellows, and the lecture was part of their first preparatory session for a study tour to Japan. To these young students, many of whom had never been to Japan, I presented a conceptual overview of the country through four lenses: continuity; the lingering influence of animistic thinking; diversity; and aesthetic sensibility.

1. Continuity – A Defining Characteristic of Japan

Continuity is a key concept that exemplifies Japan’s cultural identity. One of the most prominent examples is the Imperial Family. The current Emperor is the 126th in a long line of succession, making Japan’s imperial household the oldest continuous monarchy in the world. This tradition also includes the art of waka poetry, with successive emperors composing their own poems:

「高き屋に登りて見ればけむり立つ民の竈は賑わいにけり」

Takakiya ni / Noborite mireba / Kemuri tatsu / Tami no kago wa / Nigiwainikeri

“To my palace heights, I climb and gaze out at rising smoke—The homes of my people are prosperous indeed.”

(Emperor Nintoku, 16th Emperor)

Takakiya ni / Noborite mireba / Kemuri tatsu / Tami no kago wa / Nigiwainikeri

“To my palace heights, I climb and gaze out at rising smoke—The homes of my people are prosperous indeed.”

(Emperor Nintoku, 16th Emperor)

「君がため春の野にいでて若菜つむ我が衣手に雪は降りつつ」

Kimi ga tame / Haru no nō ni idete / Wakana tsumu / Waga koromoda ni / Yuki wa furitsutsu

“For you, I go to the fields to pick the spring’s first greens, as snow falls on my sleeves.”

(Emperor Kōkō, 58th Emperor)

Kimi ga tame / Haru no nō ni idete / Wakana tsumu / Waga koromoda ni / Yuki wa furitsutsu

“For you, I go to the fields to pick the spring’s first greens, as snow falls on my sleeves.”

(Emperor Kōkō, 58th Emperor)

ここにても雲居の桜咲きにけりただかりそめの宿と思ふに

Kokonitemo / Kumoi no sakura / Sakinikeri / Tada karisone no / Yado to omouni

“Even here, beneath the distant sky, the cherry blossoms are in full bloom, though I think of this place as only a fleeting refuge.”

(Emperor Go-Daigo, 96th Emperor)

Kokonitemo / Kumoi no sakura / Sakinikeri / Tada karisone no / Yado to omouni

“Even here, beneath the distant sky, the cherry blossoms are in full bloom, though I think of this place as only a fleeting refuge.”

(Emperor Go-Daigo, 96th Emperor)

よもの海みなはらからと思ふ世になど波風のたちさわぐらむ

Yomo no umi / Mina harakara to / Omofu yo ni / Nado Namikaze no / Tachi sawaguramu

“The world’s four seas are born of one womb; why, then, do the wind and waves rise in discord?”

(Emperor Meiji, 122nd Emperor)

Yomo no umi / Mina harakara to / Omofu yo ni / Nado Namikaze no / Tachi sawaguramu

“The world’s four seas are born of one womb; why, then, do the wind and waves rise in discord?”

(Emperor Meiji, 122nd Emperor)

The Ogasawara school of archery dates back to the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and its grandmaster is now the 31st of his lineage. Likewise, the head masters of the main tea ceremony schools—Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanokōjisenke—originating in the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1568-1603), have each continued for 16, 16, and 14 generations respectively. The confectionery company Toraya has a history of over 500 years, and it still features traditional sweets from various eras, such as tsubaki mochi from 1651, aoyagi from 1836, and chitose mochi from 1918.

The reason for this longevity of tradition lies in Japan’s geographical isolation as an island nation, which has largely shielded it from foreign invasions. Additionally, since the establishment of the Edo Shogunate, Japan experienced over 400 years with minimal internal warfare. Compared to the UK, another island nation only about 20 miles from continental Europe across the Strait of Dover, Japan is much more remote: about 120 miles from the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, with about 550 miles separating Shanghai and Fukuoka. This favorable environment allowed Japanese culture to preserve its traditions. The societal emphasis on tradition, conservatism, mastery of skills, and the artisan spirit has profoundly influenced the development of Japanese society and culture.

2. The Influence of Animism

When humans were still hunter-gatherers, they lived as part of nature. They believed that spirits and consciousness resided in all things—trees, stones, rivers, mountains—and worshipped nature itself. Over time, through polytheism and eventually monotheism, religions like Christianity and Islam spread across the world, and animism was largely pushed aside, though traces of it remain in many regions.

However, in Japan, animistic thinking has remained deeply rooted, primarily through Shinto. This has preserved ideas such as coexistence with nature and unity with the natural world. For example, the sacred object of worship at Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara, considered Japan’s oldest shrine, is Mount Miwa itself. Similarly, Hayao Miyazaki’s films like My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke were born from this cultural backdrop. Personally, I was reminded of the awe we should hold toward nature through the experience of the Great East Japan Earthquake. This way of thinking feels closer to the worldview and perception of nature held by ancient societies, rather than the relatively newer frameworks of monotheistic religions—in which God created the world in seven days and placed humans at the top of the hierarchy—or Chinese philosophy, which developed logical systems to unify central regions and exercise authority.

I once asked a Japanese person with deep knowledge of anime and long experience living abroad why Japanese anime resonates so strongly. Their answer was fascinating: “Young people in the U.S. have realized that adults lie. They don’t live in a world of simple good-versus-evil dualism. Good people have flaws, and even villains can be sympathetic. Anime reflects this more complex reality. In a way, American youth may find value in anime.” This brings to mind the perspective of Dr. Sampson and his insights described earlier in this essay: that humans are part of nature and must learn to love and cherish it as if it were family. I believe this worldview is profoundly meaningful.

3. Diversity

Many Japanese people think of Japan as a small country, but in reality, that’s not quite the case. The Japanese archipelago is geographically extensive. The distance from Yonaguni Island in the far southwest to the northern tip of Etorofu Island is equivalent to the distance from Paris to Jerusalem, or from San Francisco to Detroit in the United States. From the subtropical climate of Okinawa to the drift ice that arrives in Hokkaido during winter, Japan is home to a wide variety of dialects, traditional local festivals, regional cuisines featuring seafood and mountain produce, and distinctive local sake. This rich regional diversity is a defining feature of the country.

Another important aspect is Japan’s strong sense of the seasons. In Silicon Valley, for example, the weather is pleasantly sunny year-round, but this can lead to a loss of seasonal awareness. In contrast, Japan has four clearly defined seasons which greatly enrich the cultural sensibilities of the Japanese people. Words like harugasumi (spring haze), koke-shimizu (mossy summertime spring water), yama-nishiki (the “tapestry” of autumn colors on a mountainside), and yuki-akari (snow light) vividly convey the emotional essence of each season. The presence of such distinct seasonal changes is, in many ways, a rare and precious blessing in the world.

Furthermore, the “eight million gods” of Shintoism and the coexistence of the previously mentioned animistic thinking with Buddhist temples display the inclusivity of Japan’s system of values.

4. Aesthetic

Humans naturally yearn for beauty. Japanese culture has cultivated a highly refined sense of aesthetics. The cleanliness that astonishes so many visiting friends is, in a way, a natural extension of Japanese aesthetic values: something that Japanese people consider non-negotiable, a baseline standard. When my second son happened to strike up a conversation with a young Israeli entrepreneur at Los Angeles airport over the popular anime series Naruto, I asked the entrepreneur what he found appealing about anime. His answer was simple: “Because it is beautiful!” So, what has shaped the Japanese sense of beauty? Looking at the tea ceremony, which has deeply influenced Japanese aesthetics, we can identify three major contributing elements:

i) Relationship with Nature

While the Chinese people, who have lived under a great civilization shaped by the rise and fall of many ethnic groups, are conscious of 'Heaven' or 'Heaven's Mandate' and aspire toward grandeur and orderly beauty, Japanese people have lived in closer proximity to nature. The origin of their aesthetic may lie in the necessity of submitting to nature’s overwhelming power, as I experienced in the wake of the earthquake.

ii) The Elegance and Pathos of Classical Women’s Literature

The delicate beauty and emotional depth expressed by female literary figures, expressed via hiragana, gave rise to the concept of mono no aware, the poignant awareness of impermanence. These sensibilities have been passed down through written language to the present day.

iii) The Influence of Zen Buddhism, Adopted by the Samurai Class

As warriors who lived with death and practiced simplicity, the samurai embraced Zen Buddhism, a tradition that emphasized austerity and self-discipline. Perhaps the influence of Zen Buddhism, combined with traditional Japan’s view of nature and the delicate sensibility of women’s literature, was sublimated into the aesthetic ideals of wabi and sabi: tranquility, clarity, and a refined simplicity.

Living abroad, I often hear people say, “Japan is a special country. I was deeply moved when I visited.” I believe it’s the aesthetic sensibility embedded in Japanese culture that resonates with them. In anime and manga, this worldview and aesthetic are expressed through the creators’ pens, resonating with audiences around the world.

Many Japanese people think of Japan as a small country, but in reality, that’s not quite the case. The Japanese archipelago is geographically extensive. The distance from Yonaguni Island in the far southwest to the northern tip of Etorofu Island is equivalent to the distance from Paris to Jerusalem, or from San Francisco to Detroit in the United States. From the subtropical climate of Okinawa to the drift ice that arrives in Hokkaido during winter, Japan is home to a wide variety of dialects, traditional local festivals, regional cuisines featuring seafood and mountain produce, and distinctive local sake. This rich regional diversity is a defining feature of the country.

Another important aspect is Japan’s strong sense of the seasons. In Silicon Valley, for example, the weather is pleasantly sunny year-round, but this can lead to a loss of seasonal awareness. In contrast, Japan has four clearly defined seasons which greatly enrich the cultural sensibilities of the Japanese people. Words like harugasumi (spring haze), koke-shimizu (mossy summertime spring water), yama-nishiki (the “tapestry” of autumn colors on a mountainside), and yuki-akari (snow light) vividly convey the emotional essence of each season. The presence of such distinct seasonal changes is, in many ways, a rare and precious blessing in the world.

Furthermore, the “eight million gods” of Shintoism and the coexistence of the previously mentioned animistic thinking with Buddhist temples display the inclusivity of Japan’s system of values.

4. Aesthetic

Humans naturally yearn for beauty. Japanese culture has cultivated a highly refined sense of aesthetics. The cleanliness that astonishes so many visiting friends is, in a way, a natural extension of Japanese aesthetic values: something that Japanese people consider non-negotiable, a baseline standard. When my second son happened to strike up a conversation with a young Israeli entrepreneur at Los Angeles airport over the popular anime series Naruto, I asked the entrepreneur what he found appealing about anime. His answer was simple: “Because it is beautiful!” So, what has shaped the Japanese sense of beauty? Looking at the tea ceremony, which has deeply influenced Japanese aesthetics, we can identify three major contributing elements:

i) Relationship with Nature

While the Chinese people, who have lived under a great civilization shaped by the rise and fall of many ethnic groups, are conscious of 'Heaven' or 'Heaven's Mandate' and aspire toward grandeur and orderly beauty, Japanese people have lived in closer proximity to nature. The origin of their aesthetic may lie in the necessity of submitting to nature’s overwhelming power, as I experienced in the wake of the earthquake.

ii) The Elegance and Pathos of Classical Women’s Literature

The delicate beauty and emotional depth expressed by female literary figures, expressed via hiragana, gave rise to the concept of mono no aware, the poignant awareness of impermanence. These sensibilities have been passed down through written language to the present day.

iii) The Influence of Zen Buddhism, Adopted by the Samurai Class

As warriors who lived with death and practiced simplicity, the samurai embraced Zen Buddhism, a tradition that emphasized austerity and self-discipline. Perhaps the influence of Zen Buddhism, combined with traditional Japan’s view of nature and the delicate sensibility of women’s literature, was sublimated into the aesthetic ideals of wabi and sabi: tranquility, clarity, and a refined simplicity.

Living abroad, I often hear people say, “Japan is a special country. I was deeply moved when I visited.” I believe it’s the aesthetic sensibility embedded in Japanese culture that resonates with them. In anime and manga, this worldview and aesthetic are expressed through the creators’ pens, resonating with audiences around the world.

Conclusion

In June, the graduate students from Stanford visited Japan, traveling to Tokyo, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. They met with prominent figures such as former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Suntory Chairman Takeshi Shinano, and Hiroshima Governor Hidehiko Yuzaki. Their itinerary included not only major cities and historical sites but also visits to places like the shinkansen General Management Department and the NEDO facility on Osaki Kamijima Island. It was reportedly an excellent tour, with many participants describing it as a “life-changing experience.” Before the students’ departure, I showed them a photo of the 500-year history of traditional Japanese desserts at Toraya, the historic sweets shop, and in Kyoto, the students were able to try their hand at making those desserts themselves.

A year and a half ago, I wrote that “Japanese civilization has great value to contribute to the world, and Japanese culture makes the world’s culture richer and more diverse.” (Essay 4). Reflecting on Japan’s unity with nature, attentiveness to others, coexistence and inclusion of differing values, artisan spirit, and refined aesthetic sensibility, I feel even more strongly convinced of this today. However, we must not take this for granted. Some international scholars express concern and sorrow that such a vibrant civilization and culture may lose its vitality due to population decline. I believe it is up to all those who have inherited and internalized Japanese culture—whether they are Japanese, of Japanese descent, or otherwise appreciate Japan’s culture—to consciously preserve and pass on this cultural legacy. In a broader sense, this mission of cultural preservation is a contribution to humanity.

A year and a half ago, I wrote that “Japanese civilization has great value to contribute to the world, and Japanese culture makes the world’s culture richer and more diverse.” (Essay 4). Reflecting on Japan’s unity with nature, attentiveness to others, coexistence and inclusion of differing values, artisan spirit, and refined aesthetic sensibility, I feel even more strongly convinced of this today. However, we must not take this for granted. Some international scholars express concern and sorrow that such a vibrant civilization and culture may lose its vitality due to population decline. I believe it is up to all those who have inherited and internalized Japanese culture—whether they are Japanese, of Japanese descent, or otherwise appreciate Japan’s culture—to consciously preserve and pass on this cultural legacy. In a broader sense, this mission of cultural preservation is a contribution to humanity.

I, too, intend to continue doing my part in this endeavor.

In June, the graduate students from Stanford visited Japan, traveling to Tokyo, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. They met with prominent figures such as former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Suntory Chairman Takeshi Shinano, and Hiroshima Governor Hidehiko Yuzaki. Their itinerary included not only major cities and historical sites but also visits to places like the shinkansen General Management Department and the NEDO facility on Osaki Kamijima Island. It was reportedly an excellent tour, with many participants describing it as a “life-changing experience.” Before the students’ departure, I showed them a photo of the 500-year history of traditional Japanese desserts at Toraya, the historic sweets shop, and in Kyoto, the students were able to try their hand at making those desserts themselves.

I, too, intend to continue doing my part in this endeavor.

Recommended Information

- Essay Vol.1 (2023.11)

- Essay Vol.2 (2023.11)

- Essay Vol.3 (2023.12)

- Essay Vol.4 (2024.01)

- Essay Vol.5 (2024.02)

- Essay Vol.6 (2024.03)

- Essay Vol.7 (2024.04)

- Essay Vol.8 (2024.04)

- Essay Vol.9 (2024.05)

- Essay Vol.10 (2024.06)

- Essay Vol.11 (2024.07)

- Essay Vol.12 (2024.08)

- Essay Vol.13 (2024.09)

- Essay Vol.14 (2024.10)

- Essay Vol.15 (2024.10)

- Essay Vol.16 (2024.11-12)

- Essay Vol.17 (2025.01)

- Essay Vol.18 (2025.02)

- Essay Vol.19 (2025.03)

- Essay Vol.20 (2025.04)

- Essay Vol.21 (2025.05)

- Essay Vol.22 (2025.06)